In November 1991, Nikken Abe, the high priest of the Nichiren Shoshu Buddhist sect, excommunicated Soka Gakkai, its largest affiliated lay organization. Tensions between Soka Gakkai and the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood had in fact existed almost from the inception of the lay organization in 1930.

DIFFERENT WORLDS

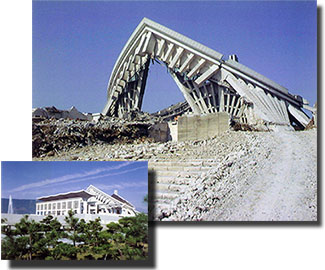

The Sho-Hondo, the main temple structure with a prayer hall seating some 6,000, was built in 1972, with donations from some 8 million people worldwide (inset). By 1999, Nichiren Shoshu demolished the building.

In the view of religious sociology scholars, the split was ultimately inevitable. As Bryan Wilson and Karel Dobbelaere state in their 1994 book, A Time to Chant: "Soka Gakkai is a mass movement, outgoing, lay in spirit, and dedicated to making Nichiren's teachings effective and practical in the everyday modern world. The Nichiren priesthood is essentially locked into an ancient ritualistic and quasi-monastic system, concerned to preserve its authority and jealous of its monopoly of certain sacred teachings, places and objects." They comment that the priesthood has distrusted the very modernity of Soka Gakkai, "...a movement of revitalization, adapted to modern conditions, pursuing from the outset a policy of expansive growth, and quickly acquiring an international clientele and orientation." [1]

Soka Gakkai has always stressed the egalitarian nature of Nichiren's teachings: that Nichiren Buddhism enables every individual, whether priest or lay believer, to develop his or her own, innate Buddha nature. It has also stressed social engagement based on the bodhisattva ideal of taking action for the happiness of others toward the creation of a peaceful global society. Nichiren Shoshu, on the other hand, has been more concerned with preserving traditional rituals, with a focus on the priests as intermediaries who are seen to be on a higher spiritual level than lay believers. In this sense it could be said to have lost sight of the original purpose and social mission of Buddhism.

THE ROOTS OF THE CONFLICT

Differences came to the fore during World War II when Nichiren Shoshu attempted to force the lay organization to enshrine the talismans sanctioned by the State Shinto system which was used by the militarist government as a means of sanctifying Japan's war effort. Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, the first president of Soka Gakkai, and his associate Josei Toda, who later became the second president, refused and, as a result, they were banned by Nichiren Shoshu from visiting the head temple. Makiguchi and Toda were later imprisoned by the government for their dissenting views, and Makiguchi died in prison. Wilson and Dobbelaere comment on this incident, writing: "Gakkai members... could uphold their own first two presidents as more ardent than the priests in protecting the true faith." [2]

WORKING TOGETHER

In the devastation of postwar Japan, Soka Gakkai enthusiastically propagated Nichiren Buddhism and rapidly increased its membership. Despite having been disappointed with the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood's compromise with the wartime militarist government, Soka Gakkai sought to develop better relations with the priesthood for the sake of the progress of Nichiren Buddhism and continued to support them--in the hope that they would help promote the common goal of establishing peace and happiness for the people. Soka Gakkai's support for the priesthood included restoration of major buildings at Nichiren Shoshu's head temple premises, construction of a new main head temple building and donation of land and a total of 356 branch temples.

AUTHORITARIAN ATTITUDE

Unfortunately, nevertheless, the priesthood, while benefiting enormously from the dramatic progress of Nichiren Buddhism pioneered by Soka Gakkai, demonstrated numerous signs of corruption and authoritarianism. When Soka Gakkai members challenged these attitudes and called for reform, the priesthood only became more adamant in enforcing the subordination of Soka Gakkai members. [3] The more Soka Gakkai grew, the more the priesthood displayed this attitude.

Soka Gakkai donated hundreds of cherry trees to the head temple (inset). By 1993, Nichiren Shoshu had chopped them down.

EXCOMMUNICATION

The clergy's move toward excommunication started in late 1990 when they launched a campaign of criticism against Daisaku Ikeda, president of Soka Gakkai International. The priesthood stated at the time that they saw Ikeda as an unfit leader with heretical views. When Ikeda publicly praised Beethoven's "Ode to Joy," for example, he was criticized for extolling Christianity.

Japan scholar Daniel Metraux comments that it became "apparent that the head temple felt that Soka Gakkai had become too powerful..." [4] Metraux attributes this friction to Soka Gakkai's interpretation of Nichiren Buddhism as expounding the fundamental equality of all people. In this respect, lay believers are apt to regard the role of a priest as being no more or less important than that of the laity.

DEMOLITION

Cranes raze the vestiges of Sho-Hondo, the main temple building (March 1999)

A 1991 letter addressed to Soka Gakkai by Nichiren Shoshu High Priest Nikken Abe asserted that statements by Soka Gakkai regarding the equality of priests and laity constituted "an act violating the doctrine." [5]

In 1991, Nichiren Shoshu, refusing requests from Soka Gakkai for dialogue, excommunicated the lay organization. The priests went so far as to cut down hundreds of cherry trees on the grounds of the head temple that were a gift from the organization. They also destroyed the main head temple building itself, a structure internationally praised for its architecture that had been funded almost entirely by the donations of Soka Gakkai members.

LIBERATION

While the excommunication served as further fodder for the scandal-mongering Japanese tabloid media, Soka Gakkai experienced the excommunication as liberation. For one thing, the priests had viewed interfaith dialogue and cooperation as "heretical." Soka Gakkai has thus become freer to express its faith in modern terms.

While its basic Buddhist practice of reciting the Lotus Sutra and chanting "Nam-myoho-renge-kyo" has not changed, since 1991 Soka Gakkai has released itself from its previous religious formalism, and more vigorously pursued its promotion of social engagement and interfaith dialogue.